Acceptance Voting

Last updated December 27th, 2025

Definition

Acceptance voting is a voting method similar to approval voting that features a distinction between acceptance and preference.

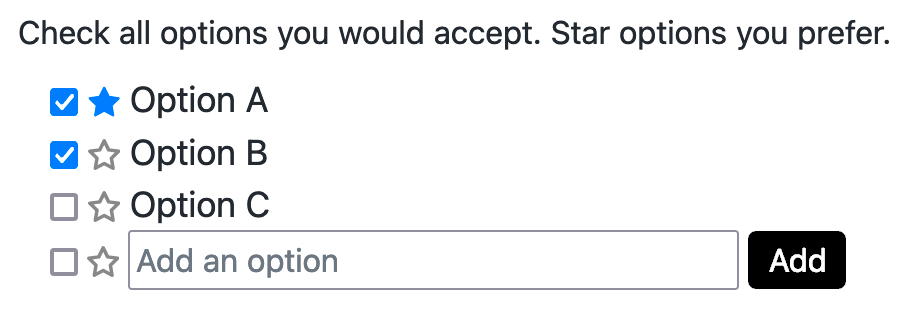

For each option, voters indicate first whether they would accept the option and second whether they prefer the option. The winning option is the one with the greatest acceptance, and if there is a tie then the winning option is the one with the greatest preference.

Mechanically speaking, acceptance voting is equivalent to two rounds of approval voting where the first round is labeled “acceptance” and the second round is labeled “preference”.

Filter first, then select

What makes acceptance voting useful is its ability to filter the option set before considering voter preferences. There are many use cases where filtering first is desirable or even required.

The following are some examples of ways you might interpret the concept of acceptance as a filter.

Voting on which options to vote on

Acceptance = “I recognize this option as valid”

When the list of options is generated collaboratively, such as in an open-ended brainstorming session where participants are encouraged to suggest whatever ideas pop into their heads without filtering, some ideas might be considered invalid for one reason or another. Filtering the ideas down to a set of options that are most recognized as valid may be necessary before making a selection.

Solving for constraints

Acceptance = “This option satisfies my constraints”

In some cases, the logistical feasibility of each option must be verified before a selection is made. For example, when scheduling a meeting, you might need to ensure that all attendees can actually attend at the times listed before you consider which time would be most convenient.

Maximizing participation

Acceptance = “I will participate in the group if this option is chosen”

Sometimes the outcome of a group decision determines who will choose to participate in the group and who will not. If the goal is to maximize the number of participants, it makes sense to filter based on which options lead to the most participants.

Minimizing harm

Acceptance = “This option would not cause me harm”

It is possible for an option that is maximally beneficial to the majority of voters to still be harmful to a minority of voters. Filtering the set of options down to the least harmful before selecting the most beneficial from that subset solves this problem.

For example, if a group of friends are voting on what to eat for lunch and nearly everyone wants seafood, but one of the friends has a severe seafood allergy, then eating seafood would cause harm to that friend. Filtering the list of options down to the ones that meet everyone’s dietary restrictions eliminates this issue.

Voter-defined criteria

Acceptance = “I accept this option according to my own definition of acceptance”

The concept of acceptance can encompass multiple meanings simultaneously. As a default, the definition can be left open-ended so that voters can decide for themselves how to interpret the concept and what their acceptance criteria is.

Asymmetric utility

The ‘filter first, then select’ approach is helpful in cases where there is asymmetric utility. For example, it is often the case that harm is worse than benefit is good because harm is more difficult to reverse. It is harder to rebuild trust than it is to destroy it. There might be an option that yields higher net utility in the short-term, but if it does so at the cost of eroding trust between the individual voters and the group, then it may yield lower net utility in the long run.

From this perspective, acceptance voting allows groups to prioritize the minimization of harm first, and the maximization of benefit second.

Origins

Acceptance voting originated from the process of designing and testing the group decision-making feature in the software application that would eventually become Harmonic.

Approval voting was the original voting method used in the app, but several problems kept popping up in small groups:

- Ties were frequent in small groups, and breaking ties through random selection felt unsatisfying.

- Voters with a large stake in the outcome were often outvoted by voters for whom the outcome did not really matter.

- Occurrences of the Abilene paradox (i.e. somehow selecting an option that nobody actually wants) were unresolvable through voting alone, even if everyone realized what was happening.

The solution to these problems that worked best came from reinterpreting the singular concept of approval as two distinct concepts: acceptance and preference. The resulting voting method worked surprisingly well, solving all of the problems listed above.

Problems with acceptance voting

TL;DR, acceptance voting works best in non-competitive contexts where group members are reasonably trustworthy.

While acceptance voting addresses the problems with approval voting described above, it is not without tradeoffs.

For example, dishonest voters who lie about which options they would accept can gain an advantage over honest voters who express their true willingness to accept options they do not prefer. In everyday life, we encounter this kind of deception in competitive negotiation scenarios like haggling over the price of an item where the buyer or seller can bluff by claiming that their preferred price is their “final offer” when really they would be willing to accept further compromise.

For this reason, acceptance voting works best in non-competitive contexts where relative honesty can be assumed. If there is competition between group members that creates strong incentives to lie, approval voting is likely a more appropriate voting method, especially when the list of options being voted on is determined beforehand.