Just Doing

August 23, 2024. original tweet thread

This is a 3 part thread about Just Doing, an approach to taking action that I’ve been trying to figure out ever since I was a kid and my parents would yell at me to “just do it” whenever I asked why I had to clean my room or whatever, as if it were obvious what “just do it” meant. I still don’t know what it means, but I’m just going to write this thread anyway.

Each of the 3 parts tries to answer a question:

- Part 1: What is self-control really?

- Part 2: Where does motivation come from?

- Part 3: How do intentions translate into actions?

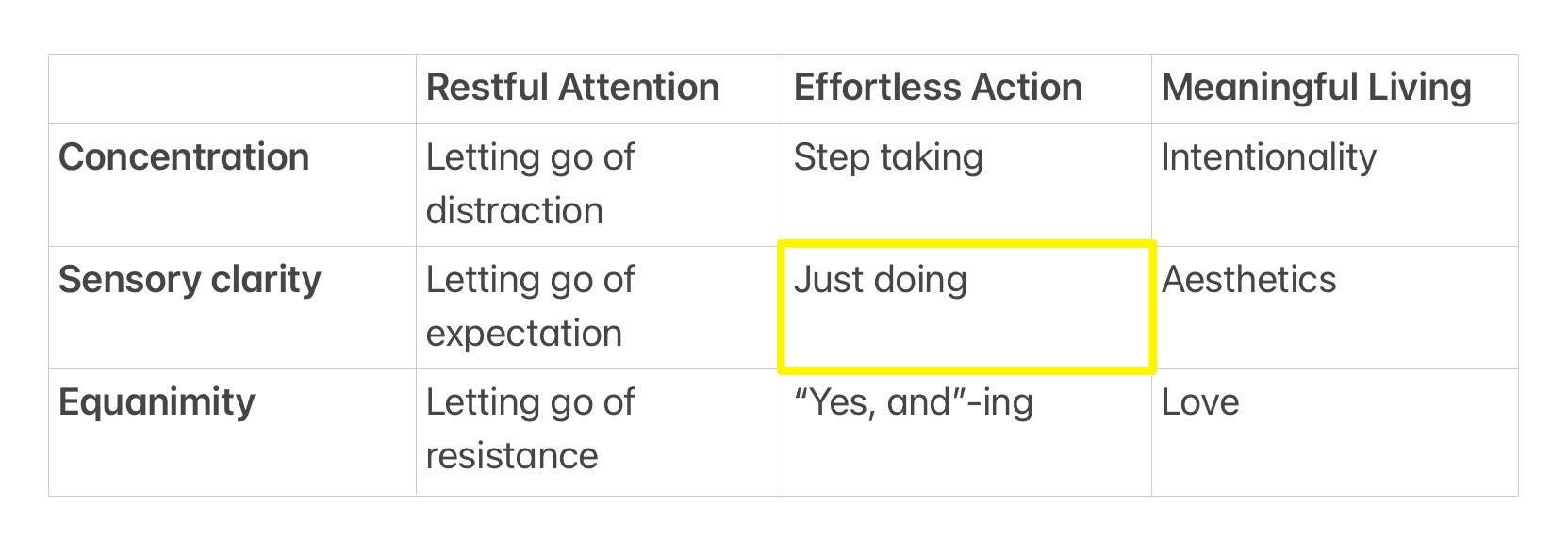

Just Doing is part of a larger framework (illustrated in the image below) that I use as a guide for being and living my life, based on Shinzen Young’s 3 aspects of mindfulness.

I’m starting this thread now as a publicly visible placeholder and will add each of the 3 parts to the thread as I complete it. These ideas have been bouncing around in my head for too long. So I’m designating this thread as the target destination to focus their expression on.

Part 1: What is self-control really?

Something has always bugged me about the concept of self-control, and it is this: who exactly is the controller, and who is being controlled? The concept implies inner conflict as a premise. If there were no inner conflict, there would be no need for control. But even worse, it’s unclear who this conflict is between. In order for there to be conflict, there must be at least two parties involved, but a self is supposed to be a singular thing. What gives?

This idea of self-control goes back at least as far as Plato’s allegory of the chariot, in which the human psyche is represented as having three parts: good horse, bad horse, and charioteer. This maps more or less directly onto Freud’s id (bad horse), ego (charioteer), and super ego (good horse). In the allegory of the chariot, the charioteer is the one who does the controlling, and the horses are the ones being controlled. The charioteer needs to control the horses because the chariot goes wherever the horses go.

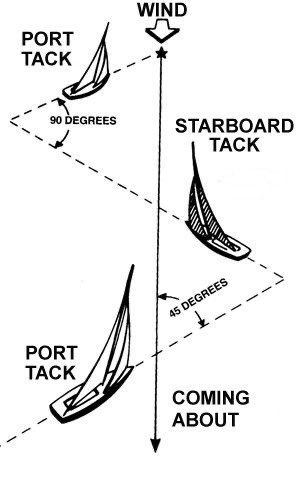

This model is fine I guess, but I’d like to propose a different model that I’ll call the allegory of the sailboat. In the allegory of the sailboat, the wind is the source of energy that propels the boat forward. But unlike the charioteer controlling the horses, the sailor makes no attempt to control the wind. Instead, the sailor adapts to the wind. The sailor is able to do this because, unlike a chariot, a sailboat can redirect the energy it captures from its energy source. Modern sailboats can even travel against the wind using the same physics that airplanes use to travel against gravity.

So what does this allegory say about the concept of self-control? One thing it implies is the absence of inner conflict. The sailor accepts the wind regardless of which direction it’s blowing. There’s no good wind or bad wind. It’s just wind. There’s no control per se, only redirection of energy. Self-control is self-redirection.

This reminds me of the expression “energy flows where attention goes”. Maybe self-control really just boils down to focusing your attention on something. And when you get distracted, you notice it, let it go and redirect your attention back to the thing. Over and over and over. Each time you get distracted and notice that you’ve been distracted, the force that pulled your attention away has given you some of its energy, which you can then redirect back towards your attention target.

But what about when we do experience inner conflict? What does the sailboat allegory have to say about that?

As mentioned above, modern sailboats have the ability to travel against the wind using the same physics that airplanes use to travel against gravity. But sailboats can only travel against the wind at an angle, not directly. So if you want to travel directly against the wind, you have to travel in a zig zag pattern. That is, at any given moment, you’re never traveling directly against the wind, but the net effect of your zig zag movements over time is that of traveling directly against the wind. I think this is a good way to think about the experience of inner conflict. You may need to approach your target obliquely by aiming for different targets that are easier to achieve. Small wins. Over time, those small wins add up to what you were originally aiming for.

And what do we do when there’s no wind?

This is something we will look at in Part 2 when we investigate the concept of motivation.

Part 2: Where does motivation come from?

Before we get to motivation, let’s talk about shoulds, as in “I should do this” or “I should do that.”

Shoulds are like structures, but not like energy. Continuing with the sailboat allegory from Part 1, shoulds constitute the shape of the sailboat and the orientation of the sails, but they are not the wind.

Shoulds are not bad. Shoulds help you make decisions about what to do and which direction to go. But they do not motivate you to follow through on those decisions. They help you steer the ship. But they don’t help you move it forward.

So if shoulds are not the wind, then what is? This is a tricky question, so let’s start with literal wind before we get to metaphorical wind. What is wind? It’s sort of mysterious, difficult to predict, near impossible to control. It doesn’t have a singular cause. It is inextricably integrated with the atmosphere as a holistic system. It doesn’t have clearly defined boundaries. It’s invisible, yet its effects are obvious. It is external, yet we must constantly breathe it in to stay alive.

From a metaphorical perspective, the best description of what the wind represents that I can come up with comes from the famous Calvin and Hobbes comic in which Calvin explains his actions to Hobbes using the words “I must obey the inscrutable exhortations of my soul.” Inscrutable exhortations of the soul are the wind that moves the sailboat.

If you pay attention to the felt sense of these inscrutable exhortations, you may notice that they seem to be felt most strongly around the heart and the lungs. Not always, necessarily. I don’t really know, and I suspect it’s different for different people and at different times. But the heart and lungs seem to me like the default zone of resonance for these inscrutable exhortations.

Motivation, then, occurs when the wind makes contact with the sails. That is, when the inscrutable exhortations combine with the shoulds.

When they’re both going in the same direction, then it’s smooth sailing. When they’re opposed, then you have a choice to make. As mentioned in Part 1, it is possible for modern sailboats to travel against the wind by zig zagging. But the question is, is that really the direction you want to go? Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t.

There’s also a third possibility, which is the absence of wind. What do you do when it feels like you can’t get motivated to do much of anything? You just feel stuck or depressed. The inscrutable exhortations seem to have gone silent.

In these cases, I think it’s helpful to get really clear about your intentions. What are your intentions exactly? If the wind was blowing, what direction would you want to go? Why? Do those intentions resonate?

Does the wind seem to have any opinions about your intentions?

Just because the inscrutable exhortations are inscrutable doesn’t mean you can’t have a conversation with them. In Part 3 we will look at how such conversations can unfold.

Part 3: How do intentions translate into actions?

If you’ve ever woken up after sleeping on your arm such that your arm went completely numb, then you know how weird it feels to try to move a part of your body that normally responds immediately to your intentions and watch it just sit there. You know how much heavier your arm feels when it’s numb and you can’t control it. It can be surprising, like “wow I didn’t realize how heavy my arm actually is”. But once you regain sensation in your arm, it feels light again.

Now for a thought experiment. Imagine what it would be like to wake up not just with a numb arm, but with no memory of ever having sensation in your arm. Imagine forgetting that it’s even possible to move your arm. You wake up with a heavy numb arm and that just seems normal. You have no memory of it ever being any other way. From your perspective, that’s just how arms are.

Now imagine gaining sensation in your arm seemingly for the first time. At this point, one of two things can happen.

The first is that you notice the sensation but you fail to realize that that means your arm is now under your conscious control. You go about your day with a heavy limp arm as expected and maybe you feel annoyed that now it hurts when your arm bumps into things. But other than the pain, not much is different than what it would be like if your arm was still numb.

The second thing that could happen is that you do realize that you can now move your arm with your mind. It’s hard to believe at first. It feels like magic. Your arm feels so light. How is this possible? It doesn’t make any sense. You are simultaneously baffled and empowered. You start to wonder what else you might be able to control with your mind that you couldn’t before.

What separates these two scenarios? How does the realization of conscious control come about? One thing we can say is that the realization of conscious control first requires the realization of the possibility of conscious control, that is, the realization that the assumption about not having conscious control might be wrong. Another thing it requires is the willingness and curiosity to try it out, to test the assumption. Finally, it requires the willingness to accept the outcome of the test, even if the outcome contradicts the assumption.

In other words, it requires lightly held beliefs and playful experimentation.

Let’s return to the sailboat allegory from Part 1 and Part 2. In order for a sailboat to float rather than sink, it must be light enough to stay buoyant. And in order to move freely, a sailboat must not be anchored or tethered to any particular location. Lightness and non-attachment are required.

Likewise, in order for intentions to translate into actions, at least some degree of lighthearted playfulness is required. You must be willing to allow things to unfold as they unfold without necessarily knowing ahead of time how they will unfold or even knowing after the fact how they unfolded. How your intentions are realized might remain a mystery even after it has happened.

Consider the example of moving your arm (just normal circumstances this time, no numbness or memory loss). You can try it out right now. Intend to move your arm and then watch your arm move. How did your intention to move your arm turn into actual movement? Nobody knows! It’s a mystery! May as well be magic!

There are certainly stories you can tell about the sequence of events that transpire in the time between the initial intention and its ultimate realization. But no one really knows in any principled way how conscious intentions result in physical actions. It’s a mystery.

Ok sure (you may be thinking). It’s a mystery in theory, but practically speaking we basically understand how we do things. We make plans and exert effort and move our bodies in a deliberate way that causes the things we want to happen to happen. It’s not a mysterious process from a practical perspective.

Yeah I guess in a lot of cases there’s no need to make a big deal out of this magic that we take for granted. As long as there are no self-imposed constraints or learned helplessness going on, then sure, stick with what works.

But the question to ask is this: How do you know that the constraints you face are real if you don’t test them? What if you’re living your life on hard mode simply because you’re assuming that easy mode is not an option?

The fact is we can never know for sure whether anything is ever what we assume it to be. There’s always the possibility that our assumptions are incorrect. And the most direct way to discover which assumptions are incorrect is through playful experimentation.

There’s a lucid dreaming technique known as reality testing. It’s a technique that you practice while awake (or so you assume). You designate some trigger action like washing your hands or touching a door knob or something like that. Then, whenever you perform this action, that’s your cue to ask yourself “Am I dreaming right now?” and you look for clues that would indicate whether you are dreaming or awake. You might try looking at your watch, looking away, and then looking back to see if the time has changed in an unusual way. You might try turning the lights off and back on again. Anything to help you discover some unusual counterexample that challenges your assumption that you are awake. Eventually you will find yourself performing this technique in a dream and you will realize that you are dreaming.

You can apply this same technique to become lucid within systems of self-imposed constraints that seem real but are actually not. Instead of asking yourself “Am I dreaming right now?” you ask yourself “What are my assumptions about this situation, and what would be a potential counterexample that would challenge those assumptions?” And then you attempt to discover such a counterexample.

Cool. What does this have to do with intentions translating into actions again?

To reiterate, the process by which intentions translate into actions is mysterious. Nobody really knows how that happens. But clearly that translation happens somehow, at least sometimes. So our goal in each case is to discover the path of least resistance between our starting point and our intended destination. And we do that through playful experimentation, which might require us to update our beliefs about the constraints we perceive. The path that leads us to our intended destination might not be visible at first.

Summary

Part 1

- Q: What is self-control really?

- A: Redirection of attention

Part 2

- Q: Where does motivation come from?

- A: The place where inscrutable exhortations of the soul push up against shoulds

Part 3

- Q: How do intentions translate into actions?

- A: By a mysterious process that is discovered through playful experimentation

Conclusion

Ok. We got through all three parts of this thread about Just Doing and not once have I actually mentioned Just Doing.

So here it is, the conclusion that this whole thread has been building up to …

How to Just Do stuff:

- Clarify your intentions.

- Repeatedly redirect your attention to the playful discovery of how your intentions might be realized.