Collective-player Games

Last updated April 5, 2025

This page is work in progress. More explanation will be added eventually.

Definition

Collective-player games are games in which individual “players” are collectively controlled.

Collective-player ≠ Multiplayer

The concept of collective-player games is different than the concept of multiplayer games. Collective-player games can be either multiplayer or single-player.

The categorization of a game as either multiplayer or single-player depends on how many players there are from the internal perspective of the game (i.e. the perspective from within the game), but the categorization of the game as collective-player or not collective-player depends on how many individuals in the external context map to a single player in the internal context. Games that map external to internal players one-to-one are not collective-player, while games that map external to internal players many-to-one are collective-player.

Examples

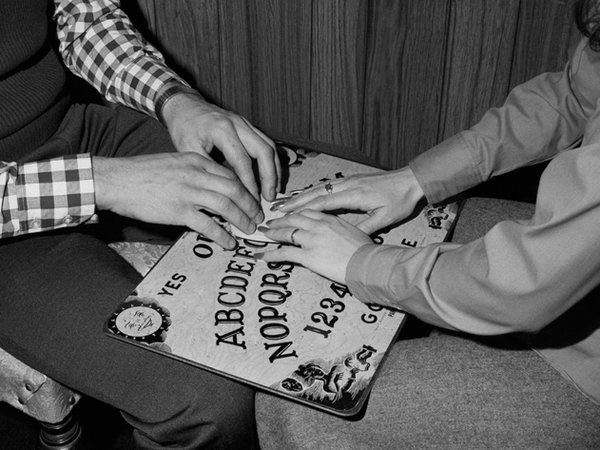

The most popular example of a collective-player game is the Ouija board in which two or more people use their hands to control a single object that acts as the “player” that chooses letters on the board to spell out messages.

Another example is the “collaborative control” Pong game experiment described here by Amy Goodchild in a blog post.

In 1991, Loren Carpenter (co-founder of Pixar), ran an experiment at SIGGRAPH. People entered a theatre to find paddles had been left on their seats, with one green side and one red side. As they held up the paddles, red and green squares appeared on a screen at the front of the theatre. Audience members were able to identify their own paddle in the crowd on the screen.

Then a game of Pong appeared and the audience came to realise that they had been split into two halves, with each team controlling one of the players in the game collaboratively, using their paddles – green for up, red for down.

Each group operated as a cohesive entity to control their player in the Pong game. In the BBC documentary ‘All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace’, Loren describes this effect:

“They’re all acting as individuals, because each one of them can decide what they’re going to do. There’s an order that emerges that gives them kind of like an amoeba like effect where they surge and they play. I wanted to see if no hierarchy existed at all, what would happen? They formed a kind of a subconscious consensus.”

A General Framework

In the examples above, the mechanism of group decision-making and coordination is unclear, and each collective member must figure out for themselves how it works through experimentation and feedback.

But what if we could design a general framework for rapid group decision-making that reliably yields coherent action sequences without depending on the adaptive learning capabilities of the members of the collective? That is what we aim to do here.

The Output

To start, let’s define the output of this framework. Games take place in time that is measured in discrete steps, whether it’s frames in a video game or turns in a turn-based game. At each time step, a decision is made by at least one player about what action to take, even if the decision is to do nothing.

The output of this framework is one action per collective per time step, selected from either a finite list of possible actions or a continuum of possible action values.

The 3 Components

The 3 components of this framework are as follows:

- Signal aggregation (memory)

- Signal interpretation (decision-making)

- Action triggers (execution)

Signal Aggregation (Memory)

Signal aggregation refers to the ability of the collective to receive and remember multiple signals that will later be interpreted. There must be some sort of shared memory that each collective member can modify independently of the other members.

In games where there is a finite list of possible actions, the signals from each collective member could be a list of actions that member would accept as the final selection. If the game takes place over a computer network, there could be a central server that receives requests from clients containing their chosen actions and stores those actions in a database to be processed in the next step.

Signal Interpretation (Decision-making)

Once signals have been aggregated, the resulting aggregation must then be interpreted so as to arrive at a single decision.

For cases where there is a finite list of possible actions, the interpretation can be as simple as tallying up the votes using a method like acceptance voting. For cases where there is a continuum of possible action values, some sort of averaging or clustering algorithm might make more sense.

In games that are not computer games, the changing state of the game environment itself can potentially serve as the interpreter, such as in the Ouija board example. Alternatively, one or more collective members can serve as representatives who do the interpreting, or there may be some predetermined rules that are enforced by a referee of some kind.

Action Triggers (Execution)

Once the decision of which action to take has been made, all that is left to do is take the selected action.

In games where time steps are independent of player actions, the trigger is simply the passing of time. For example, in realtime video games that run at 60 frames per second, an action is taken for each frame.

However, in games such as turn-based games where the progression of the game depends on when players choose to take their actions, the trigger is not so simple. In this case, members of the collective must signal not only their desired actions but also their readiness to execute. There are multiple ways this could be achieved. For now, we will leave it as an exercise for the reader. However, we will eventually update this document with more helpful ideas.

Framework Application Example: Collective-player Chess

[TODO]