Strategic Acceptance Voting

Last updated: Wednesday July 23, 2025

Note: this is a rough draft excerpt from an attempt at a more comprehensive formal analysis of acceptance voting in the context of social choice theory. Some parts are incomplete. I’m publishing this section of the paper now because I don’t know if or when I’ll ever get around to finishing it. I’ve also written a general intro to acceptance voting here.

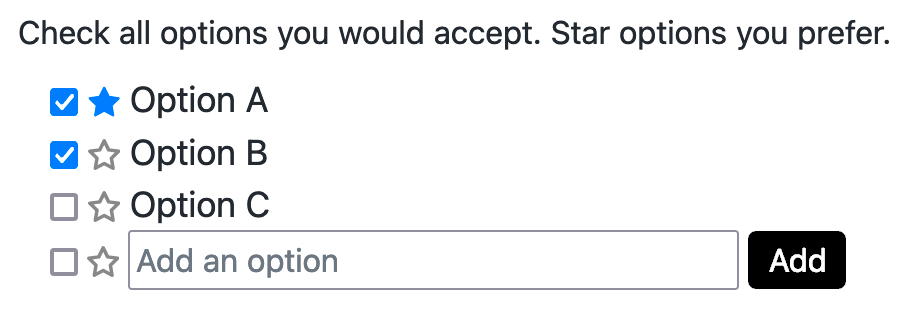

While the distinction between acceptance and preference provides many benefits, it also creates an incentive for strategic voters to misrepresent their true willingness to accept options that they do not prefer. A dishonest voter can claim to only accept their preferred options in order to gain an advantage over honest voters who share their true willingness to accept options that they do not prefer.

This type of dishonesty also occurs in various forms of informal negotiation. For example, in the case of haggling over the price of an item, both the buyer and the seller can bluff by claiming that their preferred price is their “final offer” even though they are secretly still willing to accept additional compromise.

The incentive to vote strategically depends on multiple factors including the perceived costs and payoffs of strategic voting and also the predicted behavior of other voters. This scenario can be analyzed using a prisoners dilemma model.

[TODO: analysis]

Different Perspective, Different Strategy

Winning vs Discovering

While it may seem like the incentive to vote strategically is high, there are costs to the strategic voter that are not well captured by the traditional prisoners dilemma model. To understand what these costs are, we must consider two different ways that voters understand the purpose of voting. The first way is to think of voting as a competition where voters win if they get their preferred outcome. From this perspective, the purpose of voting is to win. This framing is well represented by the traditional prisoners dilemma model that we have already explored.

The second way is to think of voting as a process where voters pool their individual preferences in order to discover what the group itself prefers. From this perspective, the purpose of voting is to discover. This perspective frames the group itself as an agent that has preferences that are dependent on but also distinct from the preferences of the individual voters. Voters are like the cells in a multicellular organism.

Notice that this second perspective introduces ambiguity about the motivations for strategic voting. If strategic voters are themselves part of the group, then who exactly are they defecting against? This ambiguity calls into question the assumptions of the traditional prisoners dilemma model.

Extending Prisoners Dilemma

In order to address this ambiguity, we need a better model. Here we will consider the extended prisoners dilemma model developed by Lakshwin Shreesha, Federico Pigozzi, Adam Goldstein, and Michael Levin in their paper Extending Iterated, Spatialized Prisoners’ Dilemma to Understand Multicellularity: Game Theory With Self-Scaling Players. This extended model adds two additional actions to the classic prisoners dilemma model, resulting in four possible actions that a player can take. These four actions are: cooperate, defect, merge, and split. Both merging and splitting change the number of players in the game, and thus the payoff matrix changes depending on the choices of the players.

If we think of voters as cells that have the ability to merge into multicellular groups that themselves have the ability to either merge into even larger groups or split into smaller groups, then we can apply the extended prisoners dilemma model using the four actions of cooperate, defect, merge, and split.

However, because our concern here is only with the incentives of individual voters, we will not be considering the group level incentives. Rather, we will treat the group as one singular entity and define merging and splitting from the perspective of individual voters.

Merging and Splitting

In the context of making a group decision through acceptance voting, we will define merging and splitting as follows.

A voter merges (or stays merged) with the group if the set of options that the voter accepts includes the option that the group selects.

A voter splits (or stays separate) from the group if the set of options that the voter accepts does not include the option that the group selects.

As a real world example, we can imagine a group of friends deciding on a restaurant to eat at for lunch. If one of the friends has a fish allergy, then that friend would not accept a seafood restaurant and would therefore be excluded from the group if the group chooses to go to a seafood restaurant. They would have to find somewhere else to eat, separate from the group.

Inclusion Good, Exclusion Bad

As Shreesha et al observed in their simulations, cells with sufficient memory tend to merge into larger and larger multicellular groups over time, eventually becoming a single unified organism. This observation aligns intuitively with human notions of the benefits of social belonging. All things being equal, being part of a group is preferable to being alone. Therefore, to keep our analysis here simple, we will assume the voter receives a positive payoff if they are included in the group (merge) and a negative payoff if they are excluded (split).

This simplifying assumption allows us to focus specifically on the incentives for strategic voting at the level of individual voters without needing to worry about the interaction between individual level incentives and group level incentives. In real world scenarios, the two levels do interact as seen in, for example, alliances between political factions. However, these complex scenarios are outside the scope of this paper.

The More The Merrier

Another simplifying assumption we will make is that the payoff from group inclusion is positively correlated with the size of the group. The larger the group, the larger the payoff. This is important to note because it implies that strategic voters do not just want to maximize their own chances of being included in the group, but everyone’s chances.

This implies that the largest possible payoff occurs when there is full consensus and therefore everyone is included in the group.

Incentivized Honesty

The consideration of both group inclusion and group size as relevant factors for strategic voting changes the payoff structure such that voters are incentivized to maximize their own and others’ chances of being included in the group by maximizing the number of options they accept. In this case, the strategic voter will accept all options where the predicted benefit of being included in the group exceeds the cost of accepting the option. In other words, the strategic voter votes honestly as long as the expected value of acceptance is positive. In cases where the benefit of inclusion is perceived as exceptionally high, strategic voters may even accept options that incur significant personal cost. In other words, they will “take one for the team” in order to remain included and maximize the inclusion of others.